I don’t know about you, but I can’t wait to get my hands on some fucking gourds and arrange them in a horn-shaped basket on my dining room table. That shit is going to look so seasonal. I’m about to head up to the attic right now to find that wicker fucker, dust it off, and jam it with an insanely ornate assortment of shellacked vegetables. When my guests come over it’s gonna be like, BLAMMO! Check out my shellacked decorative vegetables, assholes. Guess what season it is—fucking fall. There’s a nip in the air and my house is full of mutant fucking squash.

I may even throw some multi-colored leaves into the mix, all haphazard like a crisp October breeze just blew through and fucked that shit up. Then I’m going to get to work on making a beautiful fucking gourd necklace for myself. People are going to be like, “Aren’t those gourds straining your neck?” And I’m just going to thread another gourd onto my necklace without breaking their gaze and quietly reply, “It’s fall, fuckfaces. You’re either ready to reap this freaky-assed harvest or you’re not.”

Carving orange pumpkins sounds like a pretty fitting way to ring in the season. You know what else does? Performing a all-gourd reenactment of an episode of Different Strokes—specifically the one when Arnold and Dudley experience a disturbing brush with sexual molestation.

(Hat tip to Abbas Raza at 3QuarksDaily)

It’s Fucking Fall

October 23, 2009Yes I said yes I will Yes

October 22, 2009Suddenly, I’m alone. For the first time today, I find myself in a pocket of almost preternatural calm. There’s nothing left to do except get married. The first instinct of my monkey mind is to summon a wave of anticipatory anxiety, to bathe in last minute worry about details, details, details. Nervousness offers a sanctuary to hide from the suddenly overwhelming ritual. Around the slight bend of the red brick path, I can almost see that a hundred and twenty of my favorite people are waiting for us. I am the groom – standing at the front of the line of the bridal party only moments before the processional. It is a beautiful October evening and despite an entire afternoon of dark threatening clouds, we are assembled outside on the bank of the Potomac at the historic Elkridge Furnace Inn.

Time has been playing funny tricks on me all day long. I woke up late – at my leisure for once, instead of at the request of an alarm clock – and had found myself without much to do. There are two types of wedding chores – the kind that can be done before the wedding and the kind that can’t. An eighteen-month engagement had given us plenty of time to handle the former and, by contract, we couldn’t show up at the wedding site until much later in the afternoon to handle the latter. My bride had her makeup and hair and nails and spa visit to manage. After a quick shower and a peck on the cheek, she was out the door. I had but a few spare minutes before my brother, my best man, arrived and my own afternoon of errands began.

It had all started in an empty room on a Monday in June. It was the four year anniversary of our first kiss – a suitable occasion from which to measure our time together. Maggie and I had discussed marriage, but the conversation always ended without resolution. Neither of us was opposed, but there were always plenty of logical arguments to be made for postponing. We wanted to travel. We needed more money. Neither of us is of a religious persuasion, and so the historical and spiritual sacrament seemed more empty ritual than meaningful symbol. Furthermore, we both were well versed in the history of marriage as a patriarchal institution more concerned with wealth and political power than the far more recent invention of courtly love.

Family pressure certainly made sure that the marriage question rarely went undiscussed at family functions. I would protest this point under public question, but the constant questioning certainly helped to impart momentum to a prospective proposal. If I was going to act, I needed a worthwhile event and the upcoming anniversary might be the last opportunity for some time to come.

Never afraid to admit my limitations, I had asked her best friend to go ring shopping with me the weekend before. We share finances, so I had to conspire with the IT department at her work to ensure that she couldn’t check the bank balance online before dinner on Monday.1 I called ahead to the Milton Inn and they were gracious enough to give us a romantic table by the fireplace in the beautiful 18th century waystation-turned-restaurant. Getting dressed, I tucked the ring into my suit coat pocket with a covert glance over my shoulder. I was so convinced that the machinations of my conspiracy had been unsuccessful that I wrote a note for proof (“She knows!” on the back of a white envelope, as we were walking out the door.) And after dinner yet before dessert, I managed to convince my nervous fingers to open that small box without shaking and uttered a few simple heartfelt words. Yes, she said. I found my Penelope.

It is amazing how quickly people expect you to begin plotting details. On the way home from the restaurant, both my mother and hers asked us, unabashedly, if we had set a date. To set a date implies that locations have been found (there are ceremony locations and reception locations and sometimes both); ceremonies require officiants; receptions need caterers; caterers need tables, chairs and place settings; guests demand alcohol and deserve favors; a bride should have a dress, the groom a suit. There is a wedding party to assemble, bachelor and bachelorette parties to survive, wedding vows to write, a photographer to find, table settings to arrange and publish, invitations to select and draft and purchase and address, afterparties to arrange, limos to schedule, hotel rooms to book, a rehearsal dinner and a honeymoon to plan (and pay for). That is just the list of what has to be done before the wedding day. The day of is a flurry of activity that might be planned but can’t ever be thoroughly rehearsed with all its minutiae. Navigating the wedding party through Friday afternoon traffic on the Baltimore beltway, fastening boutonnières, shining shoes, and remembering all the sundry pieces of strange clothing that make a wedding outfit.2

These issues – and the seemingly infinite complexities that descend from each single one – had occupied my attention for months. With mere seconds to go before I led the processional, the cacophony of voices was reaching a schizophrenic crescendo when a single, seemingly trivial question arrested the chorus – what do I do with my hands? I couldn’t put them in my pockets. I couldn’t cross my arms. I could handle the million myriad details, but I had never once given a bit of thought to the basic mechanics of actually walking down the aisle! I was going to look like a fool. We might as well call it off. Just as quickly, the strings of our harpist rang in a familiar chord, my hands settled comfortably at ease at the small of my back, my shoulders straightened, and with a smile I stepped.

Despite my best efforts at mindfulness, there are a blur of faces. I should be prioritizing where I spend my attention, but before there is any time to strategize, I am taking my position at the altar beside our officiant Felicity. There have only been a few occasions in my life with the same feeling of imminence, of presence. I recall a particularly clear night in Tibet, sweeping granite steps with a well-worn broom. There is a moment at the top of a small peak in the Brooks Range in Alaska, staring north towards the Arctic Ocean and watching the dirty gray of a wolf track a meal across the tundra. These moments felt the same way – I am utterly here, in a moment of profound psychic importance. For perhaps the first time, I begin to experience the sheer power of the ceremony on a deeper level than mere intellectual comprehension. The confluence of events has a reality greater than the sum of its parts and the wedding is now more substance than symbol.

My brother is walking down the aisle alone, his goofy grin a shield against the nerves that I’m sure he feels. Krisis not supposed to be walking alone. Behind him, standing slightly off the brick path into the ceremony’s courtyard, our mother is standing and looking forlorn (and forgotten). My brother was so nervous that he walked right past her as she waited! As he gets close enough for an impassioned whisper, I make eye contact and find that I can only laugh “Forget something?” and look back at Mom. Suddenly much more nervous, he retreats around the edge of the courtyard, offers his arm to our mother, and makes another trip down the aisle to the gentle laughter of our assembled guests. After sitting her in the front row, he takes his place to my side.

Elizabeth is next. She is Maid-of-Honor and Maggie’s best friend. They have known each other since they were five years old. Elizabeth introduced me to Maggie when we lived and worked together in Rehoboth Beach. And she is stunning, dressed head to toe in lavender and wearing a mask of calm serenity that I’m certain is a facade. At the rehearsal last evening, her high heels made it especially difficult to navigate the cracks that pervade the old brick. Ringbearer and flower-girl follow behind – they are Elizabeth’s much younger brother and sister, aged 9 and 11 respectively. They exude a hyperactive juvenile energy as they try to restrain their hops and skips into patient steps. They are a hit, and there is much more laughter.

Her choice of a wedding march is surprisingly traditional but nonetheless beautiful, the gentle tones of Pachelbel’s Canon call Maggie and her father around the bend of the path. She is my Penelope, both my Aphrodite and my Athena, and the Persephone to my Hades. Plato’s words spring to mind uncalled, “She is wise and she touches things in motion,” as the sea of guests spring to its feet and coo. And then I am shaking her father’s hand, Maggie is beside me, and the world is at rest.

The words Felicity speaks are of friendship within the context of relationship and marriage. She is passionate about its importance and as she speaks her sentences begin to find a cadence. She relies on her notes less, and there is a rhythm that becomes its own power. She calls upon the congregation to bless our union with their approval and I am genuinely moved by the fervor with which our friends and families embrace our bond. We wrote our own vows and as we said them, a wind blew off of the Potomac and stole them from our guests’ ears. I will spare you their sappiness.

Both our ceremony and our officiant are without denomination. Felicity is a friend of Maggie’s father who, through the course of planning our wedding, has become our friend as well. She likes to proclaim that she was ordained “by the Internet” although in fact she is ordained by the ultra-liberal Universal Life Church that just so happens to ordain people online. We consulted a dozen references in search of ceremony material, found our favorites and adapted them to our purposes. Maggie and I had some difficult finding a suitable ritual within the ceremony, wanting something absent too much traditional Christian symbolism that still had authentic value. Water rituals and candle rituals and flower rituals – all had some element of cliché or kitsch that made them difficult to embrace. Some were too unwieldy to accomplish outside in the wind and the failing sunlight. We finally settled on a sand ritual – a six-liter glass vase which we would fill with a dark sea-green and rich azure blue sand, alternating between them to create layers and patterns. As we come together in marriage, the layers represent new patterns without ever losing their original color and identity. As the last grain of sand is poured into the vase, Felicity is accepting the rings from my brother and one ritual transitions into another.

Wedding rings might descend distinctly from the ancient Egyptian tradition, but the circle – without beginning or end – has perpetually been a symbol of eternity. Our rings are simple, hers made of white gold to match her engagement ring and mine of lightweight titanium. There are a few brief spoken words that are drowned out by the feeling of the ring sliding onto my finger, the metal smooth and the feel tight. I am once again struck by the difference between the symbol as its grasped intellectually and its appearance in reality. Like most of the evening, the moment passes too quickly.

Words may create a pact but it is a kiss that seals it. The photographer reinforced to us that every kiss should he held – although mid-kiss I find myself wondering where the proverbial sweet spot should be. Half-anticipating catcalls, I hold out for one brief final moment that becomes a mental highlight. And then there is clapping everywhere and a hand thumps my back while my brother whispers congratulations in my ear. I pause only to make eye contact with Elizabeth at the altar, one brief nonverbal moment of thanks. There are champagne flutes and toasts and so many people to talk to. There are hors d’oeuvres that I barely remember, conversations that were too brief, and both friends and family that I haven’t seen in far too long. I faintly recall a delicious dinner that I only momentarily enjoyed, shots of whiskey with good friends, and much more dancing than I would have soberly anticipated. Throughout the night, I found myself staring at my bride across the room on several occasions. I took these moments while I was passing between conversations or on the way to or from the bathroom to pause and invest myself in the present. I might have been by myself for an instant, but never alone.

1My plan would never have been successful if I did not work in IT and have a dozen years of experience keeping people from going places they aren’t wanted.

2“My kingdom for a pair of cufflinks,” I found myself saying as I realized the one critical thing that I had forgotten. Fortunately, a good friend is an artist who works in wire, and he whipped up a pair of functional and attractive cufflinks in a couple of minutes’ time.

Leland Palmer

October 22, 2009Pretty much everything about the world of Twin Peaks is magic. The stable of actors is amazing — from the wonders of Jack Nance to the still chills of Sheryl Lee’s smile, to the quirky post–West Side Story Richard Beymer and Russ Tamblyn. Angelo Badalamenti’s score remains one of the most hauntingly beautiful pieces of music I’ve ever heard. David Lynch and Mark Frost made for a perfect mixture of continuity and insanity, while always knowing just how gently to pull at the strings of tension and chill the nerves.

Lost Alfred Hitchcock Interview

October 22, 2009In six parts…

You Just Can’t Trust the Hawks

September 29, 2009What people like David Brooks were saying back then was so severe — so severely wrong, pompous, blind, warmongering and, as it turns out, destructive — that no matter how many times one reviews the record of the leading opinion-makers of that era, one will never be inured to how poisonous they are.

All of this would be a fascinating study for historians if the people responsible were figures of the past. But they’re not. They’re the opposite. The same people shaping our debates now are the same ones who did all of that, and they haven’t changed at all. They’re doing the same things now that they did then. When you go read what they said back then, that’s what makes it so remarkable and noteworthy. David Brooks got promoted within our establishment commentariat to The New York Times after (one might say: because of) the ignorant bile and amoral idiocy he continuously spewed while at The Weekly Standard. According to National Journal’s recently convened “panel of Congressional and Political Insiders,” Brooks is now the commentator who “who most help[s] to shape their own opinion or worldview” — second only to Tom “Suck On This” Friedman. Charles Krauthammer came in third. Ponder that for a minute.

Just read some of what Brooks wrote about Iraq. It’s absolutely astounding that someone with this record doesn’t refrain from prancing around as a war expert for the rest of their lives. In fact, in a society where honor and integrity were valued just a minimal amount, a record like this would likely cause any decent and honorable person, wallowing in shame, to seriously contemplate throwing themselves off a bridge:

David Brooks, Weekly Standard, February 6, 2003:

I MADE THE MISTAKE of watching French news the night of Colin Powell’s presentation before the Security Council. . . . Then they brought on a single “expert” to analyze Powell’s presentation. This fellow, who looked to be about 25 and quite pleased with himself, was completely dismissive. The Powell presentation was a mere TV show, he sniffed. It’s impossible to trust any of the intelligence data Powell presented because the CIA is notorious for lying and manipulation. The presenter showed a photograph of a weapons plant, and then the same site after it had been sanitized and the soil scraped. The expert was unimpressed: The Americans could simply have lied about the dates when the pictures were taken. Maybe the clean site is actually the earlier picture, he said. That was depressing enough. Then there were a series of interviews with French politicians of the left and right. They were worse. At least the TV expert had acknowledged that Powell did present some evidence, even if he thought it was fabricated. The politicians responded to Powell’s address as if it had never taken place. They simply ignored what Powell said and repeated that there is no evidence that Saddam has weapons of mass destruction and that, in any case, the inspection system is effective. This was not a response. It was simple obliviousness, a powerful unwillingness to confront the question honestly. This made the politicians seem impervious to argument, reason, evidence, or anything else. Maybe in the bowels of the French elite there are people rethinking their nation’s position, but there was no hint of it on the evening news. Which made me think that maybe we are being ethnocentric. As good, naive Americans, we think that if only we can show the world the seriousness of the threat Saddam poses, then they will embrace our response. In our good, innocent way, we assume that in persuading our allies we are confronted with a problem of understanding. But suppose we are confronted with a problem of courage? Perhaps the French and the Germans are simply not brave enough to confront Saddam. . . . Or suppose we are confronted with a problem of character? Perhaps the French and the Germans understand the risk Saddam poses to the world order. Perhaps they know that they are in danger as much as anybody. They simply would rather see American men and women–rather than French and German men and women–dying to preserve their safety. . . . Far better, from this cynical perspective, to signal that you will not take on the terrorists–so as to earn their good will amidst the uncertain times ahead.

Project Gaydar

September 29, 2009Using online information to accurately assess sexual orientation:

Using data from the social network Facebook, they made a striking discovery: just by looking at a person’s online friends, they could predict whether the person was gay. They did this with a software program that looked at the gender and sexuality of a person’s friends and, using statistical analysis, made a prediction. The two students had no way of checking all of their predictions, but based on their own knowledge outside the Facebook world, their computer program appeared quite accurate for men, they said. People may be effectively “outing” themselves just by the virtual company they keep.

…

The work has not been published in a scientific journal, but it provides a provocative warning note about privacy. Discussions of privacy often focus on how to best keep things secret, whether it is making sure online financial transactions are secure from intruders, or telling people to think twice before opening their lives too widely on blogs or online profiles. But this work shows that people may reveal information about themselves in another way, and without knowing they are making it public. Who we are can be revealed by, and even defined by, who our friends are: if all your friends are over 45, you’re probably not a teenager; if they all belong to a particular religion, it’s a decent bet that you do, too. The ability to connect with other people who have something in common is part of the power of social networks, but also a possible pitfall. If our friends reveal who we are, that challenges a conception of privacy built on the notion that there are things we tell, and things we don’t.

They Might Be Giants

September 28, 2009Hard at work teaching our kids about science. Great collection of their recent work here:

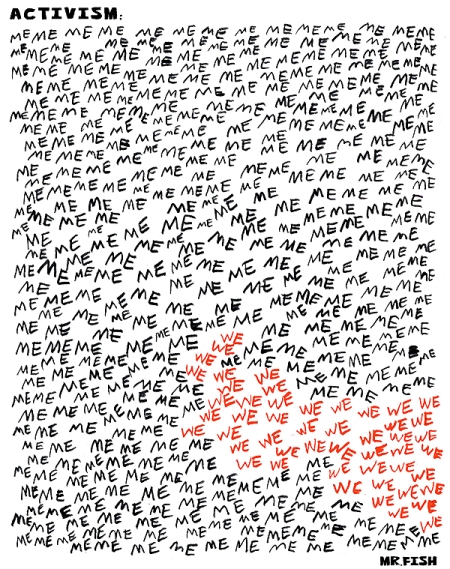

Activism

September 28, 2009Nabokov’s Final Work

September 28, 2009Knopf is publishing the book in an intriguing form: Nabokov’s handwritten index cards are reproduced with a transcription below of each card’s contents, generally less than a paragraph. The scanned index cards (perforated so they can be removed from the book) are what make this book an amazing document; they reveal Nabokov’s neat handwriting (a mix of cursive and print) and his own edits to the text: some lines are blacked out with scribbles, others simply crossed out. Words are inserted, typesetting notes (“no quotes”) and copyedit symbols pepper the writing, and the reverse of many cards bears a wobbly X. Depending on the reader’s eye, the final card in the book is either haunting or the great writer’s final sly wink: it’s a list of synonyms for “efface”—expunge, erase, delete, rub out, wipe out and, finally, obliterate. (Nov.)

Cure cancer. Eat no meat.

September 28, 2009Very interesting research indeed.

I have been working closely recently with a few extraordinary nutritional researchers, and I find that the information they have compiled is quite eye opening. Interestingly, what these highly esteemed doctors are saying is just beginning to be understood and accepted, perhaps because what they are saying does not conveniently fit in with or support the multi-billion dollar food industries that profit from our “not knowing”. One thing is for sure: we are getting sicker and more obese than our health care system can handle, and the conventional methods of dealing with disease often have harmful side effects and are ineffective for some patients.

As it is now, one out of every two of us will get cancer or heart disease and die from it – an ugly and painful death as anyone who has witnessed it can attest. And starting in the year 2000, one out of every three children who are born after that year will develop diabetes–a disease that for most sufferers (those with Type 2 diabetes) is largely preventable with lifestyle changes. This is a rapidly emerging crisis, the seriousness of which I’m not sure we have yet recognized. The good news is, the means to prevent and heal disease seems to be right in front of us; it’s in our food. Quite frankly, our food choices can either kill us – which mounting studies say that they are, or they can lift us right out of the disease process and into soaring health.

In the next few months, I will share a series of interviews I’ve conducted with the preeminent doctors and nutritional researchers in the fields of their respective expertise. And here it is straight out: they are all saying the same thing in different ways and through multiple and varying studies: animal protein seems to greatly contribute to diseases of nearly every type; and a plant-based diet is not only good for our health, but it’s also curative of the very serious diseases we face .

You must be logged in to post a comment.